在面对艰巨的社会问题时,需要有可规模化的解决方案。而如何实现规模化, Kevin Starr (Mulago Foundation )提供了一个思路:Big Enough. Simple Enough. Cheap Enough. ,你的方案是否:足够大、足够简单、足够便宜(容易)?

这有点像市场营销中的BCOS模型:

- B, benefit ;

- C, cost ;

- O, others ;

- S, self-assurance

前者从解决方案自身的特性切入(艰巨的社会问题要有 Big 方案),然后回到规模化所必需的因素:社会中为之行动(要 Simple 人们才会有持续行动)、参与各方为之买单(要 Cheap ,各方才愿意持续投入);在这里,假定的是解决社会问题之后,各方是获得受益的。

后者则基于驱动个人行动的各种因素:要有收益(不管是经济还是道德上的满足)、成本、其他因素以及自我承诺(保证)。

虽然说没有放之四海而皆准的准则,但这样类似的思路总会对一部分的问题(一部分寻求答案的人)有用。

在 Big Enough. Simple Enough. Cheap Enough. 一文中,作者的思路很有借鉴意义,不妨一记:

何为足够

在开发解决方案时,如果要达成规模化,三个问题:

那何为足够(大、简单、便宜)?答案取决于该方案的行动者(doer)以及买单者(payer)。行动者包含:

Big enough?Simple enough?Cheap enough?

- You. You develop a big enough organization to replicate at scale.

- Businesses. Lots of firms replicate your for-profit solution.

- NGOs. Lots of organizations deliver your nonprofit solution.

- Governments. Ministries and agencies deliver your solution as part of their services.

买单者:

- Customers: when you’ve got a for-profit solution

- Private Philanthropy: when your solution requires some finite subsidy

- Government: budget allocation of tax revenues or Big Aid

- Big Aid: multilateral and bilateral funding directly to NGOs

足够大

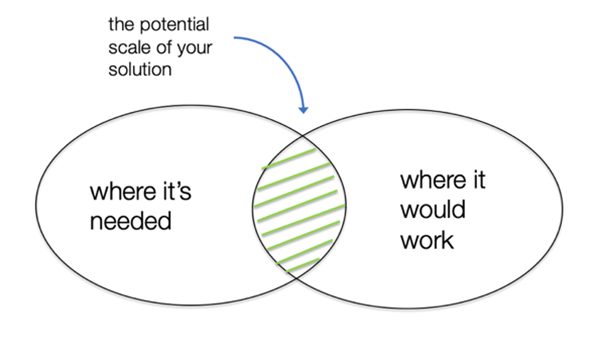

作者用了一个文氏图作了解释

在交集部分,就是 addressable market ,即可为的市场空间。

……you first have to understand the nature and magnitude of the problem you are taking on and where the need is most acute. Next you have to figure where your solution would work.

很多社会企业对此并没有明确感知:自身处于什么样的位置。如果上述文氏图对你来说太小,那么就需要重新设计(开发),重新理解。在足够大这个概念上,意味着:

- 处于方案“可为的市场空间”内的行动者是否足够多?

- 同样,买单者是否 1)资源是否充足,2)为你的方案买单?

回答 big enough 这个问题,需要的是对社会问题的精确认知,以及你对该领域的深刻理解。当然,你不一定在第一天就能得出答案。

足够简单

完整问题应该是这样的:

Is your solution simple enough for your doer to do it? You can use this as a useful design tool from day one, but proving it out requires that you replicate your solution enough times to understand just how simple you can make it.

你的解决方案对行动者们来说,是否足够简单?就如同经常被嘲笑的行为一样:在微信群里,一个陌生人发了一段话,让你到他/她的朋友圈第一条下面点赞、留言。道理如此简单:

- 你是谁?我们熟么?

- 如果不是联系人,还要加上才能操作

- 即使是联系人,凭什么呢?

- ……

这些问题搞得太复杂了,所以很多人会望而却步(置之不理)

回到行动者/买单者视角:

- 自身:在面对自身的时候,我们总会假设我们非常有耐心,能做很复杂的事。建立、运营一个大机构,筹一大笔钱。

- 商业机构可以做很多复杂的事,但是,简单依然更好。

- NGO 们对于复杂的解决方案……挑战总是让人难受,因而简单更好。

- 政府当然是越简单越好。

要怎么来界定简单,作者提供一个办法:

If you’re unsure about whether your model is simple enough, try this: Look at whatever kind of organization you have as your doer at scale—whether it’s a big international NGO, government ministry, small-to-medium enterprise, or something else—and see if you can find any that are doing a good job of delivering something as complex as your solution. Can’t find one? You’re too complicated. If you do convince yourself that there are promising organizations out there, replicate your solution by yourself a few times to get it dialed in, then partner with a real organization to deliver it in a smallish pilot.

足够便宜

完整问题是: Is your solution cheap enough that your payer would pay?

一个简单的道理就是,对比政府在某一项目上的受益者人均预算,就可以得出你的方案是否足够便宜。同理,如果你的方案成本要比市场上商业公司提供的要高,那么市场的力量就显示出来:你很可能会被淘汰。

作者下面这个观点有点残酷,但实际如此:

And don’t get swept up by your sense of what people should pay. Your admirable sense of justice doesn’t matter here, nor does your conventional cost-benefit analysis.

在这里,你自认为人们应该付出多少(为此买单)的感觉是没意义的,甚至说那符合常识的成本收益分析亦是如此。

It may be that a Ministry of Education is spending only half of what anyone based in reality would expect to pay for a decent education. It may be that your efficient $50 stove would save poor families $60 a year on charcoal. It doesn’t matter.

在预想的教育支出中,教育部门可能只支出了一半就能让任何人都享有正规的教育。你花的50元支出,可能会让贫困家庭每年节省60元的薪火,然而这并没有意义。

If you imagine that the Ministry of Education will come to its senses and spend what it should, or if you think your stove is so awesome that families will somehow transcend their day-to-day cash flow, you’re—at best—rolling the dice. Resist temptation. You’re betting the farm. Find today’s price point.

如果你想象教育部门能理智地使用其应投入的支出,或者你认为你的项目花费超出了贫困家庭的日常支出现金流,那么,最好的情况下,你只是在听天由命。